The horror of it all – waking up at 6 in the morning to make your way to an institution that sucks away 12 hours of your day. Statistically, 15% of the average lifetime is spent in school. Calvin would argue otherwise, but governments vehemently hold on to the belief that schooling truly benefits children and society at large. The market for education, a good deemed inherently desirable, would fail if the good is underconsumed – this is why governments generally make education up to a certain level compulsory (against Calvin’s wishes).

Government intervention in the form of legislation and regulation is one such method by which governments choose to deal with market failure. Governments choose to intervene to achieve economic goals such as efficiency in resource allocation and equity in the distribution of income and wealth. Beyond legislation, there are various other measures which governments may employ, to ensure the welfare of consumers (like Calvin, though to him this may seem counter-intuitive in the short-run) and producers is maximised. This blog post will explore the various methods of government intervention, their virtues and their follies.

1) Direct Provision

This refers to the government’s provision of goods and services to the public at no cost – these goods and services are effectively free for public use, and their upkeep and maintenance is generally paid for through the collection of government tax revenue.

Direct Provision is generally employed to deal with market failure in the case of public goods, where firms would not provide the good due to non-excludability and non-rivalry. Thus, the government must step in in place of the firm to provide the good, since it is inherently desirable. For instance, public swimming pools, public parks or street lighting – it is difficult to exclude non-payers, and increasing numbers of people using the goods does not decrease the quantity or quality available for others. These goods are inherently desirable – public pools can help in keeping citizens fit, public parks aid in decreasing the stress levels of people, street lighting aids pedestrians and drivers in seeing the road ahead. Thus, the government must decide in what quantities to produce the good.

There are certain limitations to Direct Provision:

- Limited funds force choices on what public goods to produce. Scarcity is an ever-present problem in direct provision, especially since the total provision of the good by the government is inevitably costly. Governments thus may not be able to provide the socially optimal level of public goods, they may under-produce.

- There is uncertainty in the calculation of expected benefits. It is difficult to ascertain the market price of these goods being directly provided, since these goods have no price (firms will not provide the goods), and thus there is no gauge of its value. Thus, uncertainty over the socially optimal level means that governments may under or over-produce, thereby failing to correct the market failure

- The direct provision is financed through taxes. Thus, there will be distortions and opportunity cost associated with acquiring these taxes, thereby potentially reducing societal welfare.

- The long-term maintenance of these goods and services requires additional use of taxpayers money, and since consumers use these goods for free, there is a possible moral hazard arising from their consumption. More risks are taken with the goods, and they may be mistreated, resulting in even more costs to the government.

2) Taxes and Subsidies

Taxes are implemented in the case of goods being over-consumed or over-produced – taxes raise the monetary cost of producing/consuming the good, thus reducing the consumption/production of the good. Subsidies, on the other hand, lower the monetary cost of producing/consuming the good, thus increasing the consumption/production of the good. Hence, subsidies are generally implemented when goods are under-consumed or under-produced.

Let us first look at taxation. The specific market failure that taxation is most commonly used to address is negative externalities, or market failure arising due to demerit goods.

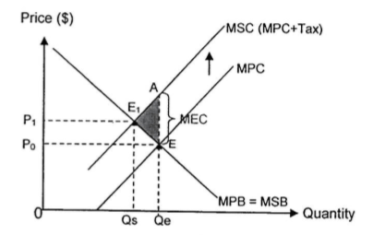

In the case of negative production externalities, the government can levy a specific tax equivalent to the monetary value of the marginal external cost (MEC). This is the monetary valuation of the harm imposed on society due to the negative externality.

In the above figure, there are negative externalities of production, due to say, the production of chemicals. Thus, there is a divergence in the marginal social cost (MSC) and marginal private cost (MPC) curves. Imposing a tax equal to the MEC results in the MPC curve shifting back to where the MSC was (MPC + Tax), as the tax has raised the firms marginal private costs at all levels of output. The tax makes the producer internalise the negative externalities, and thus, with the tax, he will now produce at Qs, where MPC + Tax = MPB. This eliminates the deadweight loss (shaded area) arising from over-production, achieving allocative efficiency.

A tax on the overconsumption of a demerit good, again, results in the consumer internalising the negative externalities. This results in the divergence of the MPC from MSC, such that MPC rises to MPC + Tax. Ideally, MPC + Tax will increase to the point where the intersection of MPB and MPC + Tax is at the socially optimal level, Qs. This would be when tax is equal to MEC, which is the amount by which MPB has diverged from MSB. Thus, the deadweight loss will be eliminated as MPC + Tax intersects MPB at where MSC intersects MSB, at Qs.

Taxes, unlike Direct Provision, have the benefit of allowing the market to continue to operate according to market forces. Furthermore, the tax revenue collected allows the government to finance other projects such as social and community development projects, that can improve societal welfare even further.

However, in practice, taxation, which, to be successful, requires the tax to be exactly equal to the monetary value of MEC, may be extremely difficult to implement due to the very fact that it is impossible to accurately value intangible external costs. Over- or under-valuing these external costs could actually lead to new social inefficiencies being achieved. Furthermore, the ability of tax to reduce consumption/production is constrained by the price elasticity of demand and supply. When demand and supply are highly price inelastic, achieving the desired reduction in output requires a higher tax compared to a good that has more price elastic demand or supply. Finally, for goods that are habitually consumed, such as cigarettes or alcohol, or even for popularly consumed goods like transport and food, a tax can be seen as unpopular, and the government must have the political will to see to the implementation of the tax at the expense of votes.

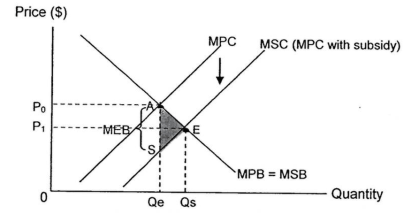

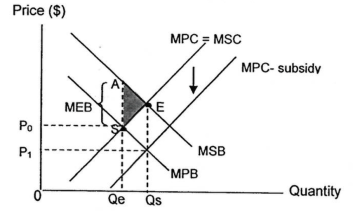

Subsidies, on the other hand, are specifically used to target goods with positive externalities, or market failure arising due to merit goods. Subsidies are used to increase the consumption of these goods. A subsidy should ideally be equal to the monetary value of the marginal external benefit (MEB).

In the case of a positive externality due to production, such as that generated by a firm that engages in R&D, a subsidy of an amount equal to the MEB to the producer will shift the supply curve from MPC to MSC. By lowering the private costs of R&D, the producer internalises the external benefits, and increases production to the socially optimal level, Qs. Thus, the deadweight loss to society (AES) is eliminated.

In the case of positive externalities due to consumption, for instance, where merit goods such as education and healthcare are under-consumed when left to the free market as individuals do not account for external benefits, subsides would lower the marginal private cost of consumption. Thus, the supply curve shifts from MPC to MPC-subsidy, and the consumption of the merit good rises to Qs, the socially optimal level, as the external benefits are internalised.

Unlike taxes, subsidies are certainly politically favourable and appealing to the public. On top of this, they can easily bring about an increase in production/consumption and are flexible enough to be adjusted according to the magnitude of the problem.

However, like taxes, since for the socially optimal level of consumption can only be achieved when the subsides are equal to the monetary value of MEB, and since the accurate valuation of MEB is difficult due to the intangibility of benefits, it is very easy to over- or under-estimate the amount to subsidise. This could lead to new social inefficiencies being achieved. Furthermore, high government expenditure is required to finance to subsidy. This requires high tax rates that can discourage investment into the country. Huge subsidies also result in high opportunity cost, as there will be less government reserves for other developmental projects.

Despite the efficacy of taxes and subsidies in theory, in reality, we still see smoking and alcohol epidemics, less than ideal levels of education uptake, and so on. At heart, there are behavioural reasons behind why economics agents make decisions, and behaviours can be hard to change, especially if only taxes or subsidies are used to achieve social optimum. Thus, measures that can overcome the problem of human behaviour may also be implemented, by ignoring human stubbornness to change entirely and forcing them to produce/consume at certain levels.

Despite the efficacy of taxes and subsidies in theory, in reality, we still see smoking and alcohol epidemics, less than ideal levels of education uptake, and so on. At heart, there are behavioural reasons behind why economics agents make decisions, and behaviours can be hard to change, especially if only taxes or subsidies are used to achieve social optimum. Thus, measures that can overcome the problem of human behaviour may also be implemented, by ignoring human stubbornness to change entirely and forcing them to produce/consume at certain levels.

3) Legislation/Government Regulation

Legislation and Regulation is the process of controlling production or consumption activities through laws and administrative rules. To decrease the production/consumption of a demerit good or a good with negative externalities, legislation can be used to force individuals to reduce individual production/consumption, such as by imposing fines or jail terms. For instance, in Singapore, it is illegal to consume or sell alcohol after 10pm in certain areas. Or, it is illegal to smoke cigarettes in one’s own home. Legislation can also be used to increase and enforce consumption/production. For instance, it is compulsory for parents to send their children to at least primary school-level education.

Legislation leaves producers and consumers no choice, and can thus be arguably more useful than taxes/subsidies. They are thus a far more commonly used method to limit negative externalities of production for goods that pollute, for instance.

However, for legislation to be effective, there must be continuous enforcement of these laws and rules, which is difficult and expensive. Furthermore, though they may be more efficient than taxes/subsidies in achieving desired outcomes, since economic agents no longer have a choice, ineffective data collection may lead to uncertainty as to how much to limit or increase production/consumption, which could again, lead to new problems of social inefficiency.

On top of that, regulation prevents the free market from functioning, and the control of goods and services in the hands of the government may lead to the unfair and inefficient distribution of resources, such as more resources being allocated towards lobbyists and those in government favour.

Besides dealing with market failure due to externalities or merit/demerit goods, legislation can also help in dealing with Market Dominance. For instance, governments may introduce price regulations such as MC or AC pricing to set prices such that the monopolist breaks even, or even makes subnormal profits for a period of time, preventing the monopolist from setting prices too high and inequitably. Legislation can also come in the form of anti-collusion laws, or laws that insist on certain standards of provision such that monopolies and large firms do not shortchange consumers.

Note that taxes and subsidies can also be used to deal with Market Dominance – imposing taxes on the average cost of firms will reduce the supernormal profits of the firm, preventing it from growing too large and increasing competitiveness. Imposing subsidies on research and development, or by reducing the MC of the firm, will allow the firm to increase output to the socially optimal level.

Taken to its extreme, legislation and regulation can take on the form of nationalisation, which refers to the transfer in ownership of a firm away from the private sector toward government ownership. Full government ownership of the production of a good aims to ensure that prices are lower and output greater than what would result from an unregulated monopoly. The downside of this is potential inefficiency of provision due to bureaucracy and the lack of a profit-making motive.

4) Education and Campaigning – Providing Information

The aforementioned solutions, though effective in their own right, are not able to correct behaviour or truly change the minds of the individual economic agent. Thus, the aforementioned solutions may not be able to tackle the market failure that is imperfect information. Without having perfect information, individuals are unlikely to change their behaviour as they cannot make informed decisions. Educational campaigns and advertising are methods by which information is made public, thus shaping the thoughts of economic agents and allowing them to be less resistant to change, thus bringing about changes in consumption/production that can help to achieve desired outcomes.

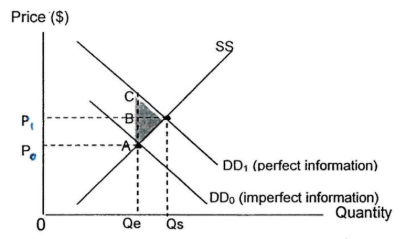

For instance, in encouraging more individuals to eat vegetables, educational campaigns that teach consumers about the health benefits of vegetables increases demand overall from DD0 to DD1 as imperfect information becomes increasingly more perfect. This allows social optimum to be reached as behaviourally, consumers have more information and now have more reason to consume vegetables, thus increasing consumption to Qs.

However, education and campaigning has its limitations. There are difficulties involved in collecting and disseminating all necessary information to consumers. Furthermore, campaign fatigue may set in if consumers are bombarded with information over an extended period of time, reducing the usefulness of this method. Funding such campaigns will also incur great opportunity cost.

In conclusion, market failure is a preoccupation on the minds of many governments – to ensure that the welfare of society is maximised, market failure must be eradicated. Thus, the four main methods – Direct Provision, Taxes/Subsidies, Legislature and Education, and the various strategies that fall under these categories all play a part to ensure that societal welfare is maximised. They are generally used in combination such that the methods make up for each others’ shortfalls.

You must be logged in to post a comment.