A crushing financial crisis in the months leading up to the 2008 United States Presidential Election shifted the nation’s focus to economic issues, and both Obama and McCain worked to show they had the best plan for economic improvement. The situation was dire; the economy had lost nearly 3.6 million jobs in 2008 and was shedding jobs at a nearly 800,000 per month rate when he took office. During September 2008, several major financial institutions either collapsed, were forced into mergers, or were bailed-out by the government. The financial system was nearly frozen, as the equivalent of a bank run on the essentially unregulated, non-depository shadow banking system was in-progress. On February 17, 2009, Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion economic stimulus package that included increased federal spending for health care, infrastructure, education, various tax breaks and incentives, and direct assistance to poorer individuals. Under his administration, though public debt increased due to declining revenue and automatic stabiliser spending, real GDP rose, inflation fell to a historically low level, and 10 million more Americans became employed.

Economic policies are the parameters within which economies function, and can also serve as solutions to looming or existing problems. Such policies are in place to improve the human condition over the long-run – this can be achieved through the speedy economic growth associated with free markets (as per the ubiquitous model of Western-style capitalism). Yet, while all economies strive to achieve economic growth, there are certainly other goals that economies aim to achieve to ensure societal stability and progress, and these goals differ from emerging economies to advanced economies. We would thus examine the various policies used to achieve various key goals, and how they vary from advanced economies to emerging economies.

Before diving into this discussion about policies, let us first look at the factors that are believed to affect growth through an examination of various growth models.

Keynesian Macroeconomics

John Maynard Keynes is widely considered the father of modern macroeconomics, and his policy responses to the Great Depression of the 1930s continue to shape our views and responses to macroeconomic shocks today. His is a model of Aggregate Demand (AD) and Aggregate Supply (AS), in which the intersection of AD and AS leads to the determination of the General Price Level (GPL) and Real National Income (RNY) of a country. The AD is calculated by the components Consumption (C) + Investment (I) + Government Expenditure (G) + Export Revenue (X) – Import Expenditure (M) (AD = C + I + G + X – M), and any change in one of these components will shift the AD, while the AS is affected by the cost of production, as well as the state (quantity and quality) of technology that changes the productivity and unit cost of each unit of labour.

Solow-Swan Growth Model

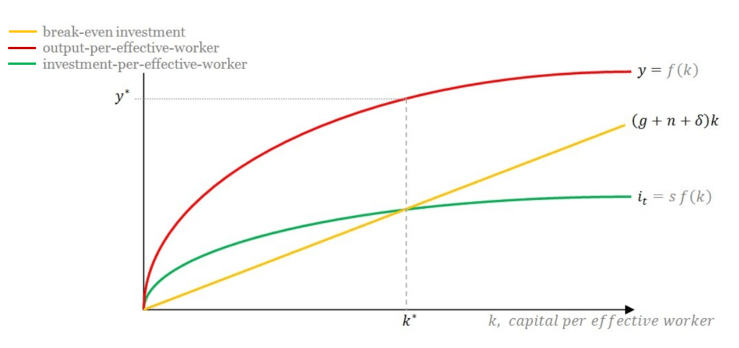

The Solow-Swan Growth Model is a standard neoclassical model of economic growth. Developed by Robert Solow and Trevor Swan in 1956, it is an exogenous growth model that recognised that the total output (Y) of an economy was a function of the capital stock (K) accumulated by the economy and the labour force (L), and (L) could be augmented by advances in technology that allowed the model to account for changes in productivity. The model plotted (y = Y/L), the output per effective worker, against (k = K/L), the capital per effective worker, as seen in the diagram below, in the red line. The savings rate (s) would determine the allocation of output between consumption and investment (i), and as seen in the diagram below, investment is plotted by the green line. The higher the value of s, the more output is allocated to investment rather than consumption, and the green line shifts upwards. Finally, the model also accounts for the break-even investment, which is the amount of investment necessary to keep (k) constant. This is allows for the determination of the steady-state rate of growth since, if (i) is above (k), then capital stock will grow, and if (i) is below (k), then capital stock will shrink. Break-even investment is plotted by the yellow line, and is proportional to (k) by the constant of proportionality (g + n + 𝛿), where (g) is the exogenous rate of growth of the efficiency of labour due to advances in technology, (n) is the rate of population growth, and (𝛿) is the rate of depreciation of capital stock. The higher (g + n + 𝛿) is, the steeper the gradient of the yellow curve, and thus the more investment necessary to keep (k) constant. If the level of investment remains constant, then (k) will fall, and a lower steady-state rate of growth is achieved.

This model has the following implications:

1. The growth rate of output in steady state is exogenous and is independent of the saving rate and technical progress.

2. If the saving rate increases, it increases the output per worker by increasing the capital per worker, but the growth rate of output is not affected.

3. Another implication of the model is that growth in per capita income can either be achieved by increased saving or reduced rate of population growth. This will hold if depreciation is allowed in the model.

4. Another prediction of the model is that in the absence of continuing improvements in technology, growth per worker must ultimately cease. This prediction follows from the assumption of diminishing returns to capital.

5. This model predicts conditional convergence. All countries having similar characteristics like saving rate, population growth rate, technology, etc. that affect growth will converge to the same steady state level. It means that poor countries having the same saving rate and level of technology of the rich countries will reach the same steady state growth rates in the long run.

Romer Growth Model

Paul Romer further developed the Solow-Swan economic growth model in his analysis. His analysis was constructed on the neo-classical production function as well. However he mainly focused on how the technological changes should be analysed. Romer’s endogenous growth model more broadly characterises capital stock to include physical and human capital, beyond just machinery, and he argues that capital does not have diminishing returns. His model asserts that the ratio of capital goods to population appears to be important over time, and it implies that countries with more labour in the knowledge sector would result in more research and development/innovation, thus allowing the country to grow faster. If we have a greater amount of the population focusing on producing ideas, we will receive a greater amount of innovation.

Recessions

Given that we started with an anecdote about the 2008 Great Recession, it would be apt to examine policies used to prevent recessions. Generally, a recession is defined as a period in which there has been a fall in GDP for two consecutive quarters. The broad category of policies used to deal with recession is stabilisation policy, which refers to policy used to stabilise a financial system or economy in two distinct sets of circumstances: business cycle stabilisation and crisis stabilisation. In either case, it is a form of discretionary policy. With respect to crisis stabilisation, as per dealing with a recession, measures are usually initiated either by a government or central bank, or by either or both of these institutions acting in concert with international institutions such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) or the World Bank. Depending on the goals to be achieved, it involves some combination of restrictive fiscal measures (to reduce government borrowing) and monetary tightening (to support the currency). This type of stabilisation involving contractionary fiscal and monetary policy can be painful, in the short term, for the economy concerned because of lower output and higher unemployment. Unlike a business-cycle stabilisation policy, these changes will often be pro-cyclical, reinforcing existing trends. While this is clearly undesirable, the policies are designed to be a platform for successful long-run growth and reform after recovery from a crisis. International institutions demand this type of policy be conducted for both advanced and emerging economies to deal with recessions, such as when Israel was recovering from the aftermath of the 1973 Yom Kippur war and it implemented the Israel Economic Stablisation Plan that successfully brought inflation to under 20% in less than two years through a significant cut in government expenditures and deficit, as well as a sharp devaluation of the Shekel, followed by a policy of a long-term fixed foreign exchange rate.

International institutions play a big part in the design of policy in response to recessions, and as we have seen earlier, much of the policy recommendations have to do with ensuring stability in the long run, involving improving confidence in a particular country’s currency, as well as building a strong financial sector to prevent recessions from happening again. This is certainly feasible in developed countries that already have a strong financial sector. The ability of developed-country governments to expand and contract their money supply through monetary policy and to raise and lower the costs of borrowing in the private sector (through direct and indirect manipulation of interest rates) is made possible by the existence of highly organised, economically interdependent, and efficiently functioning money and credit markets. Financial resources can flow in and out of financial institutions with minimum interference, and interest rates are regulated by both administrative credit controls and market forces of supply and demand, so there tends to be consistency and a relative uniformity of rates in different sectors of the economy.

By contrast, monetary policy options may be less feasible in emerging economies as markets and financial institutions are highly unorganised. In addition, many commercial banks in emerging economies are overseas branches of major private banking corporations in developed countries. Their orientation, therefore, like that of MNEs, may be more towards external rather than internal monetary situations. The ability of governments to regulate the national supply of money is also constrained by the openness of their economies, since they tend to be part of a larger global supply chain, on top of the fact that the accumulation of foreign-currency earnings is a significant but highly variable source of their domestic financial resources.

Thus, the differences in the financial sectors of emerging and advanced economies leads to differences in the policies that the two types of economies are able to employ in times of recession, as well as to avoid it. For emerging economies, in the absence of well-organised and locally controlled money markets, fiscal measures are primarily used to stabilise the economy and mobilise domestic resources. This is also particularly evident given the heavy reliance of many emerging economies on loans from international institutions – funding is their main concern (though whether or not the funding is pocketed or used properly is a separate matter altogether), for expenditure is require for short term support of failing businesses and individuals, and for the long term restructuring of the economy. For advanced economies, an entire range of countercyclical policy in the short-term and pro-cyclical policy for the long term is available, with the effectiveness of monetary policy depending on the liquidity and openness of the country, and the effectiveness of fiscal policy depending on the level of public debt in the country. For instance, Singapore is extremely prone to the influx and outflow of capital, and thus, in response to the 2008 Great Recession, it mainly employed Fiscal Policy in the form of the 20.5 billion dollar Resilience Package, to directly support low income families, as well as to help employees pay employee salaries. On the other hand, countries like the US and UK which have strong financial institutions and tend to be more closed would choose to employ monetary policy in addition to fiscal policy.

Managing Capital Flow Risks

Speaking of the strength of the financial sector, we will now examine policies to manage capital flow risks. When John Maynard Keynes and Harry Dexter White – the principal architects of Bretton Woods – were discussing the IMF’s Articles of Agreement, they clashed on many points, but they were surprisingly in agreement when it came to cross-border capital flows. Both men took as their starting point that, as White said, “the desirability of encouraging the flow of productive capital to areas where it can be most profitably employed needs no emphasis,” – but, equally, they recognized that “there are periods when failure to [manage flows] […] have led to serious economic disruption.”

Capital inflows predominantly take the form of foreign direct investment, often linked to the exploitation of natural resources. In others, private capital flows mostly correspond to public sector borrowing, either through sovereign issuances or by participation in local bond markets. In yet others, private capital flows to the economy more broadly, including to the financial, corporate, and even household sectors through debt or equity instruments. The extent to which capital flows in and out of an economy depends on multiple factors – externally, it depends on the confidence of companies and investors – in bearish times they may withdraw their investments which leads to capital outflow, in times of confidence, hot money and FDI may flow rapidly into the country. Confidence, as well as other internal factors such as interest rates, or the openness of the economy and the capital and financial account, can be affected by policy decisions.

To meet the challenges of capital flow risks would be to try to insulate the economy from foreign flows – halting or even reversing the process of capital account liberalisation. For instance, before the Asian Financial Crisis, East Asian countries were hardly in need of additional capital due to high savings rates, and the fact that these countries were generally closed off to external markets before the 1980s meant that there was little risk due to capital flows. Thus, having a high savings rate could be a method to insulate the economy from capital flow risks, especially in emerging economies in East Asia that had already begun to industrialise and slowly transition to knowledge-based economies – incomes were high enough for the government to collect sufficient tax revenue to build reserves. As per the Solow-Swan Growth Model, this lead a higher steady state growth rate and a higher level of capital. Upon succumbing to the pressure of the IMF and the US Treasury to open up their markets to the free flow of capital, the sudden outflow of capital in the 1990s as speculators attacked the Thai Baht caused currency in the region to go into freefall.

How a high savings rate can be achieved would be to increase incentives for private savings. Reducing corporate income tax and estate tax, as well as expanding tax incentives for individual retirement accounts and other retirement savings accounts would all encourage higher savings rates.

However, inasmuch as liberalisation lead to the Asian Financial Crisis, total closure to capital flows would imply foregoing all the benefits that capital flows can bring. Instead, a balanced approach needs to be adopted. Countries have implemented buffers that act as a first line of defense, such as adopting a managed-float exchange rate which allows currency to appreciate without it becoming overvalued. In addition to the savings rate to accumulate reserves to reduce the reliance on free capital flows, foreign exchange reserves can be accumulated in the face of appreciation pressure, especially if reserves are low by country insurance metrics. Sterilisation (insulating a country’s domestic money supply and internal balance against foreign exchange intervention) costs are manageable, and there is little risk of undermining the clarity and credibility of the monetary policy framework.

In the short term, especially for emerging economies that may not be able to significantly change its savings rate or build up enormous foreign exchange reserves, these countries might consider imposing an entry (or Tobin) tax, proportional to the size of the capital inflow and levied at the time when currencies are exchanged. For instance, in Brazil, a 2% entry tax on portfolio investments was imposed in October 2009, and this was meant to stop the country’s currency, the real, from appreciating further. Eventually, by mid-2011, when the tax was increased to 6%, it was found that 10% of the subsequent fall in the real was due to this intervention.

On top of all this is the rise in the adoption of a new kind of policy known as macroprudential measures, which can be applied to safeguard financial stability when inflows are fueling excessive credit growth. Mainstream economics traditionally viewed the financial system as an intermediary that was not itself a source of economic risk. Asset bubbles were deemed important only when they affected the real economy. At worst, financial institutions were channels through which economic shocks might be passed or amplified, rather than the source of the shocks themselves. Since clearly, sudden capital flows have a real, tangible effect on the real economy, there looks to be a need for tools to reduce the severity and frequency of asset bubbles and excessive credit growth. Macroprudential measures, such as improved and adjustable (or countercyclical) capital adequacy, liquidity and reserve requirements; expanded supervisory roles for regulators over a broader array of financially important companies; regulation of underwriting standards; margin regulation, all aim to mitigate risk to the financial system as a whole (or “systemic risk”). They are anti-bubble policies that aim to reduce the capital flow risks that might build up across or between institutions, what we now call systemic risks.

Fiscal Sustainability and Consolidation

Where capital flows are dealt with through building up reserves and reducing taxation so that more are encouraged to save, the implementation of these policies may bring into question the idea of fiscal sustainability. Fiscal sustainabilityis the ability of a government to sustain its current spending, tax and other policies in the long run without threatening government solvency or defaulting on some of its liabilities or promised expenditures. This is achieved through fiscal consolidation, which refers to the policies undertaken by Governments (national and sub-national levels) to reduce their deficits and accumulation of debt stock.

Advanced economies collect a much higher percentage of GDP in the form of tax revenue than emerging economies do. This is one of the reasons why emerging economies face problems of large fiscal deficits – public expenditures greatly in excess of public revenues – and this is further exacerbated by a combination of ambitious development programs and unexpected negative external shocks.

From a taxation point of view, fiscal consolidation would involve imposing taxes such that sufficient public revenue can be collected to fund public expenditure. In developed countries that, based on the Solow-Swan growth model, are experiencing steady state, and generally slower rates of growth, ensuring fiscal sustainability may prove difficult due to the slowed increase in public revenue being collected due to slowing economic growth. Thus, advanced economies may choose to increase personal income taxation on those of higher income brackets, which not only increases public revenue, but also is more progressive. Goods and services taxes can also be raised, though this may reduce consumption, and additional duties may be charged on goods that have negative externalities of consumption, such as alcohol and tobacco. Advanced economies may also be faced with the problem of burgeoning expenditures that exceed public revenue, especially with many advanced economies like Japan and Singapore being ageing populations. Thus, public spending must be restructured so that there is no excess, unnecessary spending. As in Singapore, in 2017, to further reinforce the importance of spending prudently and effectively, the Ministry of Finance applied a permanent 2 per cent downward adjustment to the budget caps of all ministries and organs of state. Austerity measures such as limiting government expenditures by limiting the perks and privileges of Ministers, and other avoidable expenditures, can also be taken.

In emerging economies, the problem with achieving fiscal sustainability is that the process of consolidation is itself inefficient. Thus, emerging economies may aim to increase the efficiency of tax administration by reducing tax avoidance, eliminating tax evasion, and enhancing tax compliance with stricter regulation and enforcement. Beyond this, they can enhance the tax to GDP ratio by widening the tax base and minimizing tax concessions and exemptions, thereby improving tax revenues. The idea of increasing efficiency applies to public spending too – in India, the Direct Benefit Transfer scheme, launched by Government of India on 1 January 2013, aimed to transfer subsidies directly to the people through their bank accounts. It is hoped that crediting subsidies into bank accounts will reduce leakages, delays, etc. Such a scheme was reported to have lead to savings of 50,000 crore rupees (or 500,000,000,000 rupees) by December 31, 2016, as per latest government figures.

Economic Growth, Domestic Consumption and Anti-Stagnation

Where there are policies to ensure sufficient tax is collected to fund public expenditure, we must also recognise that the main factor that drives the amount of tax collected is the economic growth of the country. Domestic consumption, form the perspective of AD-AS, plays an important part in economic growth, and generating economic growth will prevent the stagnation of prices in the economy. Beyond the AD-AS model, however, both the Solow-Swan and Romer growth models see a correlation between advancements in technology be an important factor for long-term growth, with the Solow-Swan model making reference to capital accumulation as another important factor, and the Romer model also placing an emphasis on innovation and research.

In advanced economies, as per the Romer model, innovation and research can be easily achieved. The existence of tertiary institutions and research facilities means more of the labour force can be employed in knowledge-based industries, and have more entrepreneurial skills, as well as the ability to earn higher wages. Thus, policy-wise, governments should encourage both process innovation and product innovation, the former making more efficient use of increasingly scarce resources, and the latter leading to improvements in the dynamic efficiency of markets. Governments can introduce tax credits for R&D and lower corporate tax, or create creative clusters/special economic zones to exploit external economies of scale. There may also be legislation to protect intellectual property rights, thus incentivising individuals to produce new products. The creation of new products and the encouragement of innovation can increase AD and domestic consumption, and prevents the stagnation of the economy.

Emerging economies, however, may not have the skilled labour or expertise to innovate and research. Thus, as a starting stepping stone for governments to create more knowledge based industries, they could consider creating state-owned enterprises (SOEs). SOEs, in addition to their traditionally dominant presence in industries that lend themselves to being naturally monopolised, such as in utilities, transport and communications, can also be active in sectors like large-scale manufacturing, construction, finance, services, natural resources and agriculture. Nationalisation can play a major role in the economies of emerging economies, as government control ensures that prices are not set above the marginal costs of producing the output, ensuring the survival of these firms that inspires confidence and domestic investment, as well as making goods affordable so as to encourage domestic consumption. Furthermore, creating SOEs enures that there is capital formation, which is important for emerging economies in early stages of development, when private savings are low. SOEs lay the groundwork for further investment in infrastructure, and remain important at later stages in industries that require massive funds.

Once SOEs have established their presence and brought growth initially, however, emerging economies may consider privatisation, since SOEs, if becoming too large, may become inefficient without a profit motive. Privatisation can broaden the base of ownership and participation in the economy, encouraging individuals by letting them feel as though they have a direct stake in the system. It also, theoretically, brings greater efficiency and more rapid growth. This can be seen in Debswana, Botswana’s diamond mining company, which is partially government owned, and partially privately owned by De Beers Mining Company, thereby ensuring the efficiency of the company and sustained employment in Botswana.

As per the Solow-Swan growth model, capital accumulation can also be carried out by emerging economies. India is now characterised as having a special niche in the world economy: providing high-tech information services. The low start-up costs in internet-empowered software programming, business processing, data transcription and a whole host of other IT-based industries means that India has become the offshoring capital of the world. This has allowed for sustained growth for India and increasing incomes for the low to middle class.

Finally, growth can not only be encouraged internally, but externally as well. Emerging economies like China have employed a “Go Global Strategy”, a national economic strategy to encourage domestic firms to invest, operate and do business abroad. Boosting international expansion allowed China to sell its goods to the global market, and also allowed for greater FDI flows into the country that have prevented stagnation, and spurred domestic consumption as China sees increasing levels of affluence.

There are certainly stark differences in the policies employed by emerging economies and advanced economies. Emerging economies and advanced economies both face constraints that limit their policy options, but one thing is for sure – that in an age of economic uncertainty, cooperation and the efficiency of international and local government institutions are of utmost importance to ensure policies could even possibly be effective in the first place. The toolkit of economic policy is vast and expansive, and as can be seen from the Keynesian, Solow-Swan and Romer models of growth, every policy can have multiple implications. Thus, to achieve various goals, policymakers must work to ensure that the negative consequences of each policy can be mitigated sufficiently, and the positive consequences can be amplified and realised.

You must be logged in to post a comment.