In 1959, vast reserves of natural gas had been discovered untapped under the city of Groningen in the Netherlands. Today, the Groningen Gas Field is the largest gas field in all of Europe, and with the privilege of that title, one would expect that the Dutch would have enjoyed a great deal of prosperity due to the sale, use and export of cheap energy. However, it was seen that in the 1970s, when the world began to take notice of Dutch gas, unemployment increased from 1.1% to 5.1%, while domestic corporate investment tumbled. Thankfully, the Dutch government had the foresight and ability to enforce expansionary monetary policy in the form of lowering exchange rates, such that economic performance was restored in the 1980s, but even this lead to more investments rushing out of the country. The impact of the episode and the interest it sparked in economists of the time lead to the coining of the term “Dutch Disease”, defined as the apparent causal relationship between the increase in the economic development of a specific sector (for example, natural resources like gas) and a decline in other sectors (like the manufacturing sector, or agriculture).

“Resources should be a blessing, not a curse. They can be, but it will not happen on its own. And it will not happen easily.” – Joseph Stiglitz

Economists have observed the spread of Dutch Disease as an ever-growing phenomenon given the rapid rise of emerging economies. The discovery of crude oil reserves in Nigeria and Ghana, for instance, have lead to a boom in the oil industry and a decline in many other primary sectors. This has brought unexpectedly poor performance to many emerging economies which, already struggling to integrate themselves into the world economy, face greater internal instability in addition to external volatility caused by globalisation. Economic institutions have done little to make full, sustainable use of the discovery of natural resources, and thus, unless a resource revolution takes place – one of awareness, consciousness, relevance and artificial scarcity, emerging economies will continue to face unexpectedly poor performance due to the very resources that seem to be their best chance of growing.

What then, were the expected, intended effects of the discovery of new resources? Natural resource discovery would naturally (haha.) lead to the development of new industries. By David Ricardo’s Theory of Comparative Advantage, countries should specialise in the production of goods that they have a comparative advantage in producing, which would be the goods that they have the lowest opportunity cost of producing. By trading these goods with goods from countries they have a comparative disadvantage in producing, countries can thus produce within their PPC, but consume beyond it, thereby increasing societal welfare. Comparative Advantage can be developed due to the discovery of factor endowments, or with an improvement in the state of technology. In the case of the Dutch, where they previously never had a comparative advantage in producing gas, with the development of new extracting and refining technology, as well as with the discovery of the Groningen Gas Fields, the Dutch could now diversify its economy, given the added sustainability of gas extraction, and develop the natural gas industry, thereby driving sustained economic growth.

There are numerous countries that lend credence to this idea. Being the second largest exporter of natural gas and the fifth largest of oil, Norway is one of the richest world economies. Botswana produces 29% of world’s gemstone diamonds and has been one of the fastest growing countries over last 40 years. Australia, Chile and Malaysia are other examples of countries that have performed well, not just despite of their resource wealth, but, to a large extent, due to it.

The key driving force that underscores the positive correlation between more natural resources and higher levels of growth is good governance and sound institutions. For most scholars, strong institutions and good governance practices have been offered as key explanatory factors to the high economic growth of these countries. Steinar Holden, Head of the Department of Economics at the University of Oslo, describes the Norwegian success as one characterized by not only strong institutions and good governance, but the protection of property rights and high quality public bureaucracy. The Norwegian model is based on the principle of transparency in the management of oil resources. It also adopted an approach of local contentism: the government aimed to award contracts to Norwegian bidders when they proved to be competitive in terms of price, quality, delivery time and service. The rationale behind this was to promote the establishment of local industry and this was achieved through cooperation with international oil companies. When foreign operators started entering the Norwegian industry in the late 1970s, they were strongly encouraged to form research and development (R&D) partnerships and joint development programmes with Norwegian companies and institutions, thus engaging in local content growth, and ensuring the sustainable, steady growth of the industry. Governmental policy meant that Norwegian oil and gas supply companies developed leading class, state-of-the-art technologies and, as a result, many international companies have located part of their R&D chain in the country. The competencies and technological expertise developed as a consequence of Norway’s local content policy also strengthened its position within the international oil industry.

Botswana shares similar characteristics with the Norwegian case. In their study titled ‘An African Success Story: Botswana’, Daron Acemoglu and colleagues observe that Botswana’s political stability with good governance practices, strong institutions, and sound policies are largely responsible for its high economic performance. Botswana has a stable political environment with a multi-party democratic tradition. General elections are held every five years. The ruling Botswana Democratic Party (BDP) has been in power since 1966, and unlike many resource-rich African states, the BDP implemented prudent policies to manage its resources, such as by purchasing and owning half of the country’s only diamond-mining company, Debswana, and directing diamond revenues into social development.

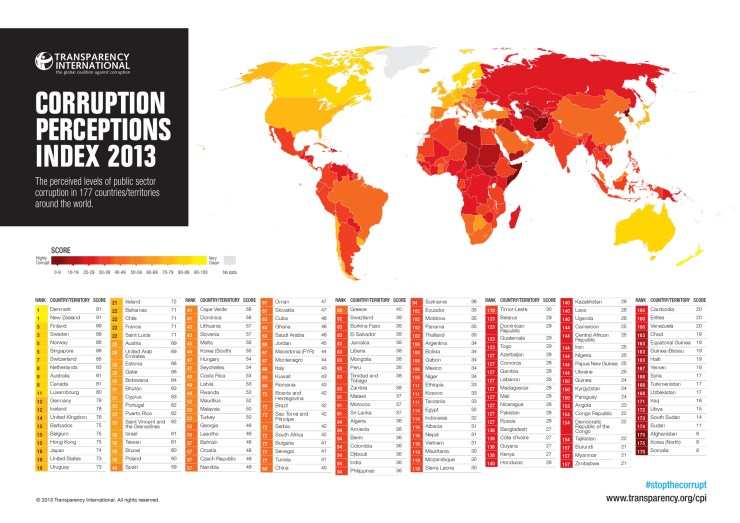

It would then seem safe to suggest that the failure of natural resource endowments in bringing economic prosperity has to do very much with the strength of government institutions. The data doesn’t lie: witness how the correlation between countries with more natural resources having poorer GDP growth aligns closely with the correlation between countries with poorer scores on the Corruption Perception Index (CPI) having poorer scores on the Human Development Index (HDI).

(see Congo, South Africa at the end of the spectrum with low GDP growth/HDI, versus Norway)

(see Congo, South Africa at the end of the spectrum with low GDP growth/HDI, versus Norway)

Upon closer examination off the CPI (as of 2013, in the figures below), especially looking specifically at the relative rankings of various South Saharan countries, we can see Botswana ranks fairly highly on the CPI, whereas other resource-rich countries that have weak government, such as Congo or Nigeria, rank lower compared to not only other countries in the world, but also other South Saharan countries.

The point being, weak government and weak policy will lead to “Dutch Disease”, as the sudden discovery of natural resources, without controlling the expansion of related industries and preventing the sudden contraction of others, will lead to unsustainable growth.

“There are twenty-three countries in the world that derive at least 60 percent of their exports from oil and gas and not a single one is a real democracy” – Larry Diamond of Stanford University.

With regards to unregulated external effects, increased revenues from natural resource exports tend to increase the real value of the exporting nation’s currency. That makes the country’s other exports, such as agricultural products and manufactured goods, more expensive and therefore less competitive in world markets. Imports meanwhile become cheaper, and this can undermine local producers and manufacturers. Taking a look at Nigeria, a country which, since the early 1970s, has seen the petroleum industry contribute about 90% to its national economy after the discovery of vast crude oil reserves. This caused a steep drop in agricultural production correlating roughly with the rise in federal revenues from petroleum extraction. Whereas previously Nigeria had been the world’s lead exporter of cocoa, production of this cash crop dropped by 43%, while productivity in other important income generators like rubber (29%), groundnuts (64%), and cotton (65%) plummeted as well between 1972 and 1983. The decline in agricultural production was not limited to cash crops amid the oil boom, and national output of staple foodstuffs also fell. This situation contrasts to Nigeria in 1960 just after independence, when despite British underdevelopment, the nation was more or less self-sufficient in terms of food supply, while crops made up 97% of all revenue from exports. In response to the drop in production, the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) government decided, under immense pressure, to implement a now notorious import license scheme which essentially involved Nigeria, for the first time in its history, importing basic food items. However, as Nigerian activist and Nobel Laureate Wole Soyinka asserts, “the import license scam that was used by the party as a reward and enticement for party loyalists and would-be supporters cost the nation billions of dollars…while food production in the country virtually ceased”. An inability and unwillingness to support the other sectors of the Nigerian economy lead to a government under immense pressure, that ultimately lead to policies that have not helped Nigeria make the most out of its oil production, let alone out of the many growing sectors of its economy.

On top of which, the economy as a whole becomes over-reliant on the natural resources that it is exporting — and this can be particularly damaging if, for any reason, there is a drop in world price for those natural resources. This was particularly noticeable in Ghana, for instance, in 2012, when oil and cocoa prices began the fall, and the government could do little to protect local firms which relied primarily on oil and cocoa export revenue.

At the same time, internally, demand also tends to rise for some service industries—such as the construction industry, since resource booms often fuel a building boom. This tends to make those services more expensive, which can hurt poorer citizens.

On top of that, international institutions, not just local governments, are also part of the problem of unexpectedly poor performance. Yes, poor governments are the dots that connect less developed countries together in the curse of natural resources, but on top of that, the inability of international institutions to make appropriate policy recommendations to less developed countries, and the inefficiency and unwillingness to work closely with local governments, means that the Dutch Disease would only continue to afflict emerging economies.

Let us take a look at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), and its role in perpetuating the Dutch Disease, as well as macroeconomic imbalance in emerging economies. The IMF was founded in 1944 for the sake of facilitating international trade. Its purpose is largely to lend money to struggling governments that cannot pay for necessary imports. It is financed largely by powerful banks attached to its larger members such as Japan, the United States and Germany. Especially for developing countries and emerging economies that ideally, should strive to achieve sustainable, inclusive growth, IMF intervention, by insisting on macroeconomic stability and financial discipline, seems to be beneficial, even necessary.

However, we should take a look at how exactly the IMF intends for countries to achieve these goals. The IMF makes short-term loans in exchange for policy changes in recipient countries. These bail-out schemes are usually initiated after crisis has arisen from government mismanagement or inadequacy – for instance, the Ghanian government said it would seek financial help from the IMF in a bid to end a deepening currency crisis exacerbated by mismanagement of oil revenues. The cedi dropped up to 40% against the US dollar this year, making it the world’s worst-performing currency alongside copper-rich Zambia’s kwacha. This was due to the government, spurred by petrodollars, buying popular support by increasing civil servant wage bills and subsiding fuel. This meant racking up borrowing, and with a booming middle class aspiring to buy foreign products, demand for imports rose, further weighing down the local currency, so public spending could not be kept under control.

The strict conditionality attached to short-term loans and financial bailout packages has a few implications. Firstly, is that the IMF has a particularly authoritarian approach to governance and the usage of funds, that infringes on the sovereignty of emerging economies. The “IMF is vilified almost everywhere in the developing world”, according to Jospeh Stiglitz, due to the encroachment of IMF schemes on national sovereignty. Despite IMF claims to political neutrality and its public support for multi-party parliamentary democracy (sometimes a precondition for loans), the Fund has historically favoured right-wing authoritarian parties and, in some cases, their actions and policies have led to the demise of left-leaning governments. It was, for example, only after the overthrow of the Unidad Popular in 1973 that co-operation with Chile was regarded as satisfactory. The IMF has found it easier to deal with authoritarian governments which have fewer qualms about executing the policies which result from the IMF’s monetaristic, laissez-faire philosophy. In the South African context, this would include wage restraint, limits on government social spending, and rapid trade and industrial liberalisation. Especially for emerging economies that seek to transition to Western-style democracy, international institutions that seek to silence the wishes of the people would be regressive and counter-productive to this aim, since a good proportion of the emerging economy population becoming more affluent and consuming/engaging in business could lead to positive spillover and trickle-down effects.

Which brings me to the second implication, that IMF policy and management by international institutions might be more counterproductive and damaging to an economy, since it exacerbates the inequality that it was trying to correct, thereby worsening instability. The first issue has to do with the economists’ basic notion of fungibility, which simply refers to the fact that money going in for one purpose frees up money for another use; the net impact may have nothing to do with the intended purpose. $1 of aid to be spent on, say, developing healthcare infrastructure for the poor, produces less than a $1 of public spending on healthcare infrastructure. The welfare-optimising response of a rational recipient government to an inflow of earmarked aid or funding, may mean that not all the money is used in the restrictive purpose as intended by the IMF, though arguably, the unfocused use of funds may have more to do with government mismanagement than the failure of the IMF (and rather than rooting out such incompetence, the IMF is funding it. The Fund’s money goes to governments that have created the crisis to begin with and that have shown themselves to be unwilling or reluctant to introduce necessary reforms.).

However, the issue of fungibility contributes to a second issue of over-reliance. The IMF’s austerity measures, coupled with the restrictive conditions on aid supplied, means that in the short run, issues with regards to inequality and unemployment caused by the discovery of new natural resources remain unsolved, without the necessary reforms and without aid being distributed in the right places, or without policy reforms going towards the more productive use of natural resources. And this is fine for the IMF, because it has a bureaucratic incentive to lend. It simply cannot afford to watch countries reform on their own because it would risk making the IMF appear irrelevant. 41 countries had been using IMF credit for between 10 and 19 years – relying on IMF’s short-term loan programme creates loan addicts, which does not truly help in the redistribution of wealth and the creation of jobs. As in the case of Ghana, where the booming petrol prices have lead to unemployment in various other sectors, and there exists widening inequality between those who own the means of production and poor labourers, the IMF agreement reached in 2015 was highly counter-intuitive, as it forced Ghana to allow its currency to depreciate even further, reduced subsidies and increased the price of utilities. The measures sought to boost government revenue and raise export earnings by making the country’s products cheaper, while raising the prices of imports. But ultimately, this hurt the spending power of both the rising affluent and the already-poor, and hindered government efforts to redistributed wealth to lower income levels. This is why Ghana decided to go ahead with extending the deal it struck with the IMF by another year, to 2019, since the IMF threatened to immediately abrogate the whole deal if they declined the proposal to extend. The IMF thus approved an additional 94 million dollar disbursement for the extension, on the condition that the freeze on government sector employment will linger on, which would undoubtedly further hurt employment in Ghana.

From the perspective of governments under the influence of international institutions, there is an element of moral hazard involved. The very presence of these international bodies and their authoritarian doctrines, their economic orthodoxy and their supposed wisdom, means that governments become eager to continue relying on IMF bailouts. The more the IMF bails out countries, the more we can expect countries to slip into crises in the future because it encourages risky behavior on the part of governments and investors who fully expect that if anything goes wrong, the IMF will come to their rescue.

Thus, international institutions, in the context of emerging economies that have seen problems arising due to the discovery of new natural resources, will exacerbate these problems with policy and conditions that are highly restrictive, and do not tackle the root causes of the problems.

But all this while, who are the parties that directly deal with the management, production and distribution of natural resources?

Multinational Enterprises (MNEs) are the final piece of the puzzle; beyond the governmental and international institutions that continue to exacerbate the problems caused by the discovery of new resources, MNEs, driven by profit, are the arms that directly contribute to the unexpectedly poor performance of emerging economies. Unlike, say, in Norway, where the oil industry is half controlled by the government, in many emerging economies, industries based off of natural resources are almost entirely privately owned. MNEs thus have control over industries that might have strategic importance to the economy, and even society.

Earlier we addressed weak governance – this is a problem that we already know is worsened by international institutions, and now, we will see how it is a problem that cannot be solved due to the existence of MNEs. Many MNEs have an annual turnover larger than the GDP of small states (eBay has a larger turnover than the GDP of Madagascar, while Nike has a larger turnover than the GDP of Paraguay). MNEs threaten national sovereignty due to the fear of capital flight – they have incredible bargaining power, and thus, governments influenced by MNEs may have a bias towards protecting the interests of important countries, failing which, MNEs may choose to pull out of the country, or not even invest in it in the first place. Arguably then, MNEs do have positive impacts on emerging economies (otherwise why would governments seek their foreign direct investment?) Their investment into the economy means that the new resources discovered can be (theoretically) efficiently and productively managed by private companies that have the technology and expertise in industries that use these resources. By allowing MNEs into the economy, the emerging economy can also become a part of the greater global supply chain, thereby receiving technological spillover effects that allow it to increase its productive capacity, as well as to enjoy sustained economic growth since it supplies to other countries in a global production process.

However, even if there is sustained growth (which we have seen to not be guaranteed if the unrestrained growth of one industry leads to the shutdown of others), such growth has no guarantee of being inclusive. Especially in emerging economies, where there is weak environmental regulation and worker protection, MNEs may be incentivised to exploit the lowest common denominator, thus leading to little trickle-down effects to individuals. Most notable is the impact of Shell’s oil refining activities in the Niger Delta – local workers for oil companies (not just Shell) frequently strike in protest of unsafe working conditions, such as oil spills and pipeline explosions, or in protest of wages. The environmental damage that the activities have caused have lead to a decreased quality of life for 500,000 Nigerians in areas like Ogoniland, where the refining activities are the most extensive. The pollution and environmental degradation has lead to unsafe drinking water, a lack of arable land, as well as increased physical injury and sickness. Worst of all, the government is powerless to stop this, since petroleum makes up 90% of the Nigerian economy, at the expense of agriculture and other sectors, and without regulation, MNEs can continue to exploit the lowest common denominator in the pursuit of profit.

Furthermore, the presence of MNEs in a resource-rich country may actually hold back the ability for emerging economies to progress even further in the long term. With the economy becoming so reliant on primary industry, technology and skills upgrading is held back, and emerging economies have very little ability to progress to more knowledge-based industries.

One thing is for sure – the resource curse doesn’t necessarily have to be a curse. The Dutch Disease and the many other hindrances to economic performance that discovering new natural resources can cause have been avoided and can be avoided, and this is not exclusive to developed countries like the Netherlands or Norway, it is happening in Botswana, Chile, and other emerging economies around the world. For now, a combination of poor governance, the obstinance of international institutions, and the uncontrolled exploitation by MNEs, leads to unexpectedly poor performance for emerging economies. Without major structural reforms, these countries will be left behind at the demise of the very policies and resources they thought would bring sustained economic growth to all.

Not to say that there’s nothing that can be done. “Real development requires exploring all possible linkages: training local workers, developing small- and medium-size enterprises to provide inputs for mining operations and oil and gas companies, domestic processing, and integrating the natural resources into the country’s economic structure” as per what Joseph Stiglitz says. Such reforms with regards to the management of resources will allow emerging economies to reap the full benefits of the natural resource discovery, and ensure the employment of workers who may be displaced should the demand for certain industries fall. Beyond this, unlike the short term loans that do not develop long term comparative advantage and efficiency, what matters is that a country develops dynamic comparative efficiency and diversifies its industries to remain adaptable to potential shocks an changes, such that volatility in emerging economies is reduced. Protectionist measures in the short term may also be considered to allow local industries to develop that will complement the major industry centered around the extraction and production of the new natural resource. At the end of the day, natural resource endowments signal new hope, and can bring new hope, if and only if, as seen from the successes of Norway and Botswana, there is strong government that considers but does not buy wholesale into the rhetoric of international institutions, and that places the welfare of people and inclusive, sustained growth first, over the profits of MNEs. Only then, would the grass be greener on the other side of Groningen.

You must be logged in to post a comment.