There’s always an amount of uncertainty when it comes to purchasing anything. At stake is your hard-earned money, and sometimes your pride, as con artists watch on gleefully while you walk away with a box of nothing that you believed to be something.

The study of information asymmetry, and in the case where consumers have less knowledge about the product that producers do, adverse selection, has shed light on market failure and inequality in the provision of and access to information. Information asymmetry leads to varying levels of uncertainty, a condition under which it is impossible to list all possible out comes, or to assign probabilities to each outcome. Thus, every economic decision is essentially a gamble, and it is up to the individual to decide what he perceives to be the most worthwhile choice. From the consumer’s point of view, various socio-economic factors, such as education levels, or the level of stability one has with regards to one’s home (owned or rented), job, etcetera all leads to varying degrees of risk-taking by different consumers. Risk is a condition under which the decision-maker can list all outcomes and assign probabilities to each one. In general, consumers can be classified into having three different attitudes towards risk:

- Risk-Averse: Risk-averse individuals will generally refuse even fair gambles in which much information is provided and profit is generally gained. Thus on average, these individuals make zero monetary profit.

- Risk-Neutral: Risk-neutral individuals are only interested in gambles in which the odds will yield a profit on average.

- Risk-Loving: Risk-loving individuals are interested in all gambles, even ones in which strict mathematical calculations reveal that the odds are unfavourable.

Attitudes towards risk, from a socio-economic point of view, are developed from one’s background. Those from wealth and who have received higher levels of education would have a better understanding of how to make informed decisions, as well as how to make returns on their money in a safe, calculated manner. With a greater understanding of information asymmetry, wealthier individuals tend to be more risk-averse. On the other hand, those of lower income levels tend to spend a higher proportion of their income to live from day to day, compared to those of higher income levels who can afford to save a proportion of their income. As well as due to lower levels of education and thus a hindered ability in making informed decisions, these individuals will thus tend to be more risk-loving, as can be seen from statistics which show that “players with incomes less than $50,000 spend more than others, and the lower income categories have the highest per capita spending” in a 1999 report published by Duke University titled “State Lotteries at the Turn of the Century.”

Governments have a duty of care towards their citizens, especially the lower income, who due to socio-economic factors that are mostly no fault of their own, tend to make riskier decisions that reduce their returns in the long run. The purchase of shoddy goods thus becomes a problem that governments need to solve, lest face the fury of citizens who have been cheated of their money, or worse, have been caused personal harm due to the purchase of these goods. There are two players involved in the transaction of shoddy goods, each with different responsibilities and rights. There is the producer of the good, who owes the consumer a duty of care under the law, as well as the consumer, who acquires certain rights to protection having purchased the good. Governments and policymakers would thus have to devise measures that ensure producers adhere to certain quality standards so as to fulfill that duty of care, in addition to measures that reinforce the rights of consumers.

Economic analysis can be useful in assisting policymakers as streamlines the devising of appropriate measures with the aim of correcting the market failure caused by the sale of shoddy goods. Dealers in goods of questionable quality have been aware of the problems of adverse selection and hidden information for years. In what was outlined by George Akerlof in ‘the Market for Lemons: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism”, he described the problem of ‘lemons’ in the used car market, the nub of his research being that “sellers of secondhand cars know a lot more about the trustworthiness of their vehicles than potential buyers, which makes buying a used car a risky proposition. The seller has an incentive to say that the car is in good shape, but if that were true, why would he be getting rid of it?” (John Cassidy) Thus, a market failure arises as the bad cars tend to drive out the good, and the only used vehicles available will be cheap duds.

Thus, to correct the market failure, policymakers would craft policies that ensure that producers sell products that they can stand by, setting a standard of quality. For instance, the Government of Victoria in Australia has implemented a used car statutory warranty in which “a licensed motor car trader must provide a statutory warranty if the car is less than 10 years old, and has traveled less than 160,000 kilometres”, on top of which, the “trader is obliged to list any faults not covered by the statutory warranty on a defect notice.” By making sellers provide information and by offering warranties, used car dealers signal to potential customers that they have confidence in the quality of their vehicles. This helps to mitigate the problem of cheating, as the product warranty becomes a sign of quality that separates the lemons from the good used cars – used car dealers whose cars do not meet minimum standards of quality will not meet the minimum requirement for a state-mandated warranty, and thus do not have the same seal of quality as other dealers, making it riskier and less profitable to stay in the market as the rational consumer would likely choose cars from dealers that offer these warranties. This strategy effectively discourages the sale of dangerous products.

Some may argue that consumers “need protection to make up for their ignorance”, citing instances in history where “before the regulation of food standards in the UK, at the end of the nineteenth century, it was common to sell bread plumped up with chalk dust and, in ale houses, beer dosed with salt so that with each mouthful the drinker became thirstier” (Jonathan Wolff). For a policymaker, one strategy would be to equip consumers with the knowledge needed to better make informed decisions, thus tackling the problem of hidden information.

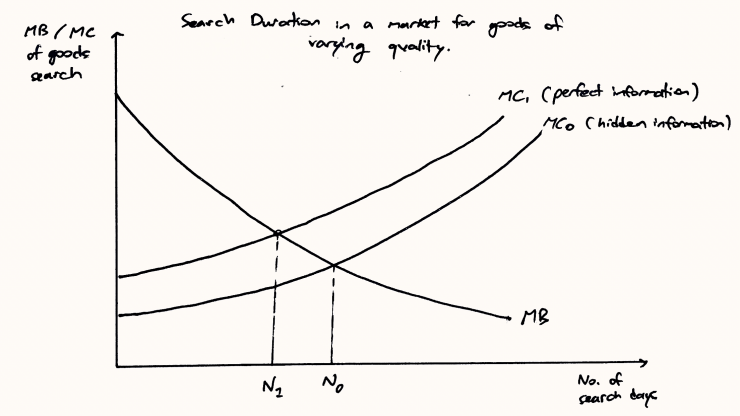

Thus, a different response to consumer ignorance is to increase people’s knowledge, “as we see with the rise of consumer groups publishing magazines to expose poor products and recommend others. These provide a market in information, a sort of espionage on behalf of the consumer” (Jonathan Wolff) The provision and acquiring of information is important in protecting the consumer, especially considering Stigler’s theory of search costs. Essentially, search theory is the study of an individual’s optimal strategy when choosing from a series of potential opportunities of random quality, given that delaying choice is costly. Eventually, people will find it too costly to seek out all information to eliminate price and quality variability. The provision of information, as has been seen in the continuing development of labeling on food, for instance, helps consumers inform themselves, reducing their search costs and reducing the marginal cost of search from MC0 to MC1, thereby reducing the optimal search length, increasing the likelihood of finding a better deal.

Both of these strategies, one which ensures that producers maintain a high standard of quality, and one in which deals with hidden, asymmetric information so that consumers can make informed decisions, are based off of economic analysis that ensure that fewer shoddy goods remain in the market, or are bought in the first place. This reduces the overconsumption of shoddy goods, thus reducing the market failure, and protecting consumers.

However, inasmuch as economic analysis can be used to formulate policy that stops consumers from buying goods and producers from selling goods that pose too high a risk of harm or death in the first place, it is difficult to use economic theory to protect consumers after the purchase of such a good, as the value of a life and the risk of damage is difficult to quantify economically.

For instance, let us look at railway safety in the UK. The approach taken is an application of what is known as risk-cost-benefit-analysis, a form of economic analysis in which the costs of any possible safety measure is weighed against its benefits. In calculating how much it would cost to introduce such safety measures, one may hazard introducing multiple figures for consideration: the number of lives that are likely to be saved, and the cost of doing so, for instance, but ultimately, it all boils down to this cold-blooded question: is it worth spending that amount of money to save each life?. The UK uses a figure known as the official value of preventing a fatality (VPF) to calculate the optimal price to pay for saving a life – that value being somewhere around 1.4 million pounds for each individual, but from a consequentialist and economic point of view, it is “probably morally wrong to have spent so much to save so few lives”. (Jonathan Wolff)

Furthermore, it can be argued that there is uncertainty in the formulation of public policy to protect consumers from shoddy goods – it is impossible to list all possible outcomes, or to assign probabilities to a good malfunctioning and causing damage to property, as manufacturers who continue to distribute and sell shoddy goods likely have few checks for quality and thus have no data for a good failing or malfunctioning. Thus, it is difficult to insure against such goods.

In conclusion, every case of damage to property or individuals caused by shoddy goods and lemons is unique and different – in a court of law damage and compensation is awarded based off of principles and past cases rather than economic analysis. Economic analysis can do little to help formulate policy to protect consumers after purchasing the good, as decisions on the amount to compensate and the rights consumers are entitled to are made based off of the law and philosophical, moral judgement that is potentially irrational and uneconomic. However, the implication is that economic analysis would be useful in formulating policy to protect consumers from purchasing goods in the first place, which involves altering consumers’ of different attitudes towards risk, generally by making them more risk-averse through supplying them with the knowledge and ability to make more informed decisions. Information asymmetry due to inequality is a market failure that needs to be corrected, be it through raising the awareness of consumers, or taking an egalitarian approach towards safety standards, ensuring that a high standard of quality for all products is met and made known to consumers, as even the poorest among us deserve equal access to information.

You must be logged in to post a comment.