Calvin and Hobbes was one of my favourite comics as a child. Known as the “last great newspaper comic”, I would, unbeknownst to me, be swept up in a world of Aristotelian philosophy, wishing I too had my own anthropomorphic tiger. I had always been caught up in Calvin’s riveting 6-year-old musings, some of which still stick with me even till today.

My parents had a single book of Calvin and Hobbes comic strips in the house. 6-year-old me would read and re-read the same book until one day, it dawned on me that there had to be more where this came from. I pleaded with dad to buy me more, begging him to bring me to a bookstore. Finally, seeing no choice other than to burst my 6-year-old bubble, my dad laid his hand down and told me that the comic was no longer in production – if I wanted the books I would have to buy them secondhand online. Together we went onto eBay, the hip new place in 2006 to spend one’s money, and to my dad’s horror, a copy of Scientific Progress Goes ‘Boink’ would set us back $100. With no concept of money I would ask him if we could get it, to which he would promptly say no.

Did I mention I had a penchant for tantrums as a kid?

“…he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention. Nor is it always the worse for the society that was no part of it.” – Adam Smith

How did the price of an innocent secondhand comic book reach triple digits?

Why would Bill Watterson no longer produce stories of his beloved Calvin and Hobbes?

Why would dad refuse to buy the secondhand comic and willingly sit through a temper tantrum?

These are questions pertaining to the decision of prices in different markets (in this case, the market for Calvin and Hobbes comics), which can be explained via the concepts of Demand and Supply, as well as related Elasticity concepts.

Remember that theoretically, a free market system is completely void of government intervention – all economic decisions are made by individuals and firms, guided by self-interest. In this way, as Adam Smith, coined the ‘father of economics’, describes, the prices in the market will be shaped by the invisible hand, where individuals, if allowed to make decisions that maximise self-interest, will lead to efficient outcomes in the market.

How did the price of an innocent secondhand comic book reach triple digits? (Demand, Supply, Equilibrium Price and Output)

The first factor that influences the price and quantity of goods in a market is demand, which is the quantity of good/service that consumers are willing and able to purchase at every given price over a particular period of time. Generally, the quantity demanded for a good falls when the price of the good rises in what is known as the Law of Demand (quantity demanded for a good is inversely related to its price). Common sense would dictate that if I wanted to buy a certain number of cans of Coke, assuming that the amount of money I’m allowed to spend remains constant, if the price of every can of Coke decreases, I would buy more cans of Coke. This is a simple illustration of the Law of Demand.

Notice how the demand curve is downward sloping. Their marginal benefit (benefit is the area under the demand curve) from consumption is decreasing, as they derive less benefit in terms of utility from each increase in quantity. This illustrates the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility (LDMU), which states that the utility gained from each additional unit of consumption decreases.

Having understood demand, the Law of Demand and LDMU, we now realise that there are multiple possible combinations of price and quantity that lie along the demand curve. Any point along the demand curve can be achieved with a movement along the demand curve, and this would be due to changes in price. A fall in price leads to an increase in quantity demanded, while a rise in price leads to a decrease.

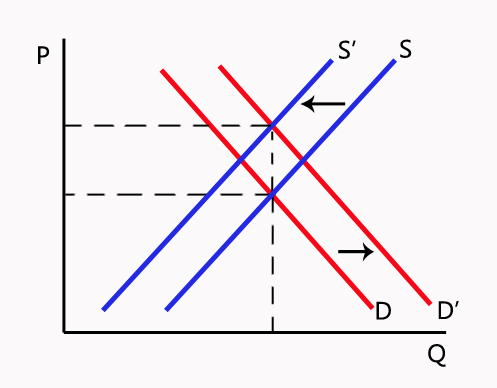

To achieve entirely different combinations of price and quantity, there needs to be a shift in the demand curve. An outward shift in the demand curve indicates an increase in demand, while an inward shift indicates a decrease. Shifts in the demand curve would be due to non-price determinants, namely changes in tastes and preferences towards certain products, changes in the level of income, or changes in the size of the population that access the market.

The second factor that influences the price and quantity of goods in a market is supply, which is the quantity of the good/service producers are willing and able to offer for sale at every given price over a given period of time. As opposed to the Law of Demand, the Law of Supply states that the quantity of a good/service supplied is directly related to its price. For instance, in producing cups of coffee, it gets increasingly expensive for producers to produce more units of coffee, possibly due to overusing resources such as baristas or coffee grinders, thus making them less efficient in production. This leads to an increase in the marginal cost of production (cost being the area under the supply curve) as production expands, and thus, an upward-sloping supply curve.

Similar to the demand curve, movements along the supply curve are caused by changes in price, while shifts in the supply curve are caused by non-price determinants, such as the cost of production, the state of technology, or the number of firms.

The intersection of the demand curve and the supply curve would determine the price at which the good should be sold at, and how much of it should be available on the market. This is because at this point, marginal cost equals marginal benefit, and thus, the self-interest of both consumers and producers are maximised, as per Adam Smith’s Law of the Invisible Hand.

So, back to Scientific Progress Goes ‘Boink’. There are two possible, concurrent explanations for the increase in price of secondhand Calvin and Hobbes comic books on eBay. The first reason is that the supply of comic books has fallen. Bill Watterson stopped the production of the comic strip, and thus, less and less books would be available for resale, leading to a fall in supply. The second reason is that the demand for these secondhand comics has risen, whether due to a change in tastes and preferences towards collecting old comics, or due to rising levels of income as the world economy grows. Thus, a higher equilibrium price would be reached. Shifts in supply and demand, would thus explain the rise in price of secondhand comics on eBay.

Why would dad, or buyers in the market in general, refuse to buy the secondhand comic? (Demand Elasticity Concepts)

$100 can buy a lot of things. Other than for secondhand comic books, $100 could buy 50 cans of potato chips, textbooks, or a month’s worth of prescription medicine. What determines how sensitive people would be to a change in price of a good, and thus determines how likely a person would buy one good over the other, would be its Price Elasticity of Demand (PED) Value.

PED is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a good to a change in its price. The value of PED ranges from 0 to infinity, with 0 indicating that the demand for a good is perfectly price inelastic (there is no change in quantity demanded in response to a change in price) and infinity indicating that the demand for a good is infinitely price elastic (a change in price leads to an infinitely large change in quantity demanded). Essentially, the larger the value of PED, the more sensitive consumers would be to changes in the price of a good.

PED alter the steepness of the gradient of the demand curve – a steeper demand curve with a larger PED value indicates that the good’s demand is price inelastic, while a gentle demand curve with a smaller PED value indicates that the good’s demand is price elastic.

PED is affected by a few key determinants. Primarily, it is affected by the proportion of income that the good takes up. More expensive goods generally take up a larger proportion of income, and thus, people would be more sensitive to fluctuations in the price of such big ticket items, staying away from them as the price increases, and being more interested in them when the price falls. The larger the proportion of income it takes up, the more its demand would be price elastic (hence, a $100 Calvin and Hobbes book, relatively expensive compared to other comic books, would have a low PED value).

It is also affected by the availability and closeness of substitutes. If the book is readily substitutible, then increases in its price means consumers can more easily switch to other goods. The more close and available substitutes the good has, the more its demand would be price elastic (hence, my dad would be unwilling to buy the book if he’s aware of the existence of say, free Calvin and Hobbes comics online). Thus, with the price of the book having increased, a more than proportionate decrease in quantity demanded would have been caused (a large movement along the demand curve). Compared to if the demand for the book was price inelastic, then the increase in price would only lead to a less than proportionate decrease in quantity demanded (a small movement along the demand curve).

The comic book, to me, was clearly a necessity in my 6-year-old mind, especially since I didn’t earn any income whatsoever. But to my dad, such a good was far from a necessity, possibly even a luxury item compared to the groceries he needed to rush off to buy. This calls to mind the idea of Income Elasticity of Demand (YED).

YED is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of demand of a good to a change in consumers’ income. The value of YED ranges from negative infinity to infinity, with a negative value of YED indicating that the good is an inferior good (an increase in income leads to a fall in demand for the good), while a positive value of YED indicating that the good is a normal good (normal in the sense that, as per the non-price determinants of demand, an increase in income leads to an increase in demand for the good).

Within normal goods exist two categories: necessities (0 < YED < 1) and luxuries (YED >1). The demand for necessities is generally income inelastic, meaning that an increase in income leads to a less than proportionate increase in demand (demand curve will shift outwards by a small amount), while the demand for luxuries is generally income elastic, meaning that an increase in income leads to a more than proportionate increase in demand (demand curve will shift outwards by a large amount). During that period of time, signs of economic downturn leading up to the 2008 Global Financial Crisis could have caused a fall in income, and the book is perceived as a luxury, then there would be a more than proportionate fall in demand for the book.

Finally, Cross Elasticity of Demand (CED) is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of the demand of a good to a change in price of another good. Like YED, the range of values for CED is from negative infinity to infinity. A negative value indicates that both the goods in question are complements (an increase in the price of one good leads to a fall in the demand for the other good), while a positive value indicates that both the goods in question are substitutes (an increase in the price of one good will lead to an increase in the demand for the other good). In the case of the Calvin and Hobbes comics, the price of accessing the comics online for instance might have fallen, leading to a fall in the demand for Calvin and Hobbes comic books, since the two are close substitutes.

We now understand how PED, YED and CED can affect demand in the market for Calvin and Hobbes comic books. My dad, being an individual whose demand is part of the summation of individual demands that constitute the market Demand Curve, would thus likely see a fall in his demand for the books, and would thus refuse to buy them.

*Take note though! I have taken careful pains in this illustration to separate the analysis of the market from the analysis of my dad’s individual consumption behaviour. Note that the tools of PED, YED and CED are meant for analysing a market, and from there, can give us an indication as to the behaviour of individual consumers or firms.

*You might also notice that in my initial analysis of Demand and Supply, demand rises, but in the analysis using PED, YED and CED, demand has fallen. This is to illustrate the fact that in economics, there can be multiple plausible explanations for the same phenomena. Your job as a student of economics is to decide (rationally) which arguments and what evidence would make for the most convincing, consistent argument possible 🙂

Why would Bill Watterson no longer produce stories of his beloved Calvin and Hobbes? (Supply Elasticity Concepts)

Finally, let us see how we can use the Price Elasticity of Supply (PES) to understand why Calvin and Hobbes has gone out of print. PES is a measure of the degree of responsiveness of quantity supplied to a change in the good’s own price. Similar to PED, the value of PES ranges from 0 to infinity, with 0 indicating that the supply of a good is perfectly price inelastic (there is no change in quantity supplied in response to a change in price) and infinity indicating that the supply of a good is infinitely price elastic (a change in price leads to an infinitely large change in quantity supplied). Essentially, the larger the value of PES, the more sensitive producers would be to changes in the price of a good.

Certain factors affect the magnitude of PES. Primarily, the length and complexity of the production process – if the production process is long and complex, requiring many man-hours and many resources, then it is difficult for a producer to respond quickly to changes in price. It is also affected by the level of stocks and inventories – if the good is difficult to store and jostles for space with other goods, then they cannot be sold as easily, making it difficult to respond quickly to changes in price. In the case of comic books, the creative process is certainly complex and long. Watterson might not have been able to find sufficient inspiration to continue writing, resulting in a lengthy production process. Furthermore, with other comic books on the rise, and publishers wanting to earn revenue selling fresh new content, the level of stocks and inventories of Calvin and Hobbes comics remains low. Thus, the supply of Calvin and Hobbes comics is price inelastic, and now, even with the high prices that the books could be sold for, Watterson may not be able to respond in time to produce more copies of his old books, or to come up with new ones.

Beyond PES, he might also have found it better and more satisfying spending time, in his old age, retreating into the woods of Ohio painting landscapes. The opportunity cost of painting landscapes (continuing to write) was something he was clearly ready to stomach when he gave up his stirp, to the dismay of many, in 1995.

“…products, like people, have a birth, a life and a death, and that they should be financed and marketed with this in mind.” – Tim Hindle

More than two decades later, Watterson’s beloved comic would still have a place in the hearts of many around the world. I have come to understand $100 was certainly a lot to shell out for a comic book (but boy, did I want to know why Scientific Progress Goes ‘Boink’), and more importantly, with economic analysis, I have come to better understand the decision-making processes behind rational economic agents like my dad (the consumer, albeit by proxy) or even Watterson himself (the producer). Tools like Demand and Supply analysis, as well as the various elasticity concepts (PED, YED, CED, PES) are all extremely useful for understanding how prices are determined in a market, and are also useful for consumers to make better choices, or for producers who aim to sell more products, as both parties can better appreciate the market conditions they face.

Does economic progress go ‘boink’ too?

You must be logged in to post a comment.