You’ve faced it before. You’re moments away from having to order a plate of mixed rice. The queue grows shorter and time runs out, while the weight of a myriad of choices grows heavier on your shoulders.

Finally, the seller asks: “boy, what do you want?” You have 3 dollars to spend, limiting your final combination of choices from a selection of 20 ingredients, your stomach growls at the idea that if you could you would simply eat everything on offer, and time is running out as patrons behind you breathe down your neck.

“economy is the art of making the most of life” – Charles Wheelan

The scenario perfectly illustrates the central economic problem: we have limited resources but unlimited wants. We all have a figurative (or in the scenario, literal) hunger to be satisfied – individuals want to maximise their utility, business want to maximise profit, governments want to remain in power for as long as possible. Yet, to achieve these wants, we find ourselves limited by the resources we possess, whether it be the capital we have (the pocket money to buy our food with), or the time we can spare before achieving that goal becomes more costly than beneficial (approximately 10 seconds before the customer behind you gets way too impatient).

This is scarcity – the central economic problem which the discipline aims to solve. Economics recognises the following to constitute our ‘limited resources’, or factors of production:

- Land – resources supplied by nature

- Labour – human effort, both physical and mental

- Capital – resources that are man-made, such as money, machines, tools or factories

- Entrepreneurship – ideas, organisation and management

“the model being used by economists [is] a model that replaces Homo sapiens with a fictional creature called Homo economicus” – Richard Thaler

To create economic models, certain assumptions have to be made such that these models have sufficient predictive power to produce consistent results. One key assumption is that of the Homo Economicus, a creature that makes only rational choices, meaning that it weighs its costs (such as how much money we can spend, or how much time we can afford) and benefits (the satisfaction gained from eating food), and within the limit resources it has, makes a choice that maximises its net benefit.

This calls into question the idea of opportunity cost. Since we are forced to choose between our wants, we are in the process forced to prioritise them. Thus, making the choice that maximises our net benefit clearly means that we forgo a whole multitude of alternatives, all of which are necessarily less beneficial to our welfare. For instance, at the mixed rice stall, suppose that with the 3 dollars, you can only choose three ingredients. Your three favourite ingredients are fish, beancurd and fried eggs. Thus, the choice that would maximise your net benefit would be to order these three items. Your fourth favourite ingredient is chicken – thus, the next best choice would be to order, say, chicken, beancurd and fried eggs. The rational consumer would choose to order fish, beancurd and fried eggs to maximise his net benefit, and thus, would forgo the next best choice that includes chicken. This is opportunity cost: the cost of any economic choice in terms of the next best alternative that has to be forgone. Thus, understanding and being able to priortise one’s choices can help someone make decisions more efficiently. It should of course be noted, that opportunity cost is subjective, and its value is clearly difficult to calculate quantitatively, especially if the circumstances change (you might like chicken on Thursdays, but fish on Wednesdays).

Our analysis thus far reveals a few key players in the economy: consumers (individuals yearning for a plate of mixed rice), producers (sellers of the mixed rice) and the government (dealing with a lot more than just mixed rice). From an governmental perspective, in deciding how much to allocate to different sectors of the economy, the central economic problem poses three questions regarding the use of scarce resources to produce goods and services for the people: (1) What and how much to produce? (2) How to produce? (3) For whom to produce?

Answering (3) would be a key determinant of economic inequality and how resources are distributed – if you’d like to see more, you can view my posts under “Thoughts | Inequality”. Answering (1) and (2) would bring to mind two key ideas: The Margnialist Principle and the Production Possibility Curve (PPC)

The Marginalist Principle essentially assumes that we make choices at the margin, weighing the marginal costs (additional cost of consuming/producing one more unit of a good) and marginal benefits (the additional benefit of consuming/producing one more unit of a good). The decision that maximises net benefit is the one where marginal benefit = marginal cost, and in this way, we ensure that our scarce resources are used to consume/produce things that we want the most. Thus, it could help answer the question “how much to produce?”

The Production Possibility Curve shows the possible combinations of output that can be produced in an economy, assuming an economy that can only produce two types of goods (in this case, guns or butter). Any point on the PPC (B, C or D) are points at which limited resources are fully and efficiently employed, a.k.a, the economy is producing at the maximum output. Producing at B means more resources are being used to produce guns than butter, while producing at C means more resources are being used to produce butter than guns.

Producing at A would denote underproduction, which is undesirable for an economy as it means that resources are being underutilised, and thus maximum net benefit is not achieved. Maximum output is only achieved on the PPC, and to move from A to any point on the curve, the economy would need to achieve actual growth (percentage annual increase in national output).

Producing at X would be impossible given the current state of the economy, as it is beyond the PPC. To reach that point, the economy would need to achieve potential growth (the speed at which the economy could grow), shifting the entire PPC outwards This would involve increasing the quantity of limited resources, whether by importing them or discovering them, or increasing the quality of limited resources, such as through technological advancement.

By understanding the possible combinations of goods that can be produced, we answer the question “what and how much to produce” as we see the trade-offs between producing different goods. By aiming to produce on the PPC (achieving actual growth), or by aiming to be able to produce more overall in the future (achieving potential growth), governments will find different methods of production and source for more resources to answer the question “how to produce”.

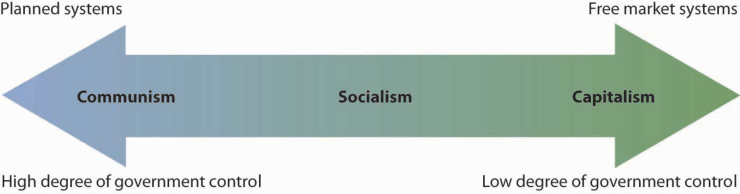

All of the above, of course, assumes a free market economy. In reality, there are many different economic systems, as seen in the spectrum below:

So at the end of the day, recognise that even in your position, standing in front of the mixed rice seller and choosing your fish, beancurd and fried eggs, that you are both contributing to the economy by providing the seller an income, as well as making an economic choice. Hopefully, by understanding the concept of scarcity, opportunity cost, and the Marginalist Principle, you would be able to make better, quicker choices, before you get chased away by the patron behind you.

Also recognise that economics is all around us – the opportunity cost of the patron waiting to queue for mixed rice could be hamburgers at a nearby McDonalds. The mixed rice seller could be using the PPC model to decide the combination of fish and chicken to produce that day. Nobody needs to be an economist to realise that economic decision-making occurs at every moment, in countless instances around the world.

Thus is the beauty of economics.

You must be logged in to post a comment.